|

| Film Title/ Director & Editor and Film Description | |||||||

|

Le Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip to the Moon) (1902) d. Georges Melies This pioneering science fiction film, a 14-minute ground-breaking masterpiece with 30 separate tableaus (scenes), was one of the earliest experiments in film. It was made by imaginative, turn-of-the-century French filmmaker/magician Georges Melies, approximating the contents of the novels by Jules Verne (From the Earth to the Moon) and H.G. Wells (First Men in the Moon). With innovative, illusionary cinematic 'editing' techniques (trick photography with superimposed images, dissolves and jump cuts), he depicted many memorable, whimsical old-fashioned images:

|

|

|||||

|

The Life of an American Fireman (1903) d. Edwin S. Porter American director and film pioneer Edwin S. Porter, chief of production at the Edison studio, helped to shift film production toward narrative story telling with such films as this one -- the first realistic (or documentary) film with continuity editing. It featured the following editing features:

The film was interspersed with scenes of the firemen responding to the sound of the alarm (a hand pulled the alarm in close-up), descending on a fire pole, and coming to the rescue in a horse-drawn wagon pumper (in exterior shots), heightening suspense. |

|

|||||

|

The Great Train Robbery (1903) d. Edwin S. Porter This 10-minute dramatic film was the first to use a number of innovative, modern film techniques, many of them for the first time, such as parallel editing, minor camera movement, location shooting and less stage-bound camera placement. It also featured multiple camera positions, filming out of sequence and later editing the scenes into their proper order. There were 14 scenes with parallel cross-cutting between simultaneous events in its narrative story with multiple plot lines. Porter's film was a milestone in film-making for its storyboarding of the script (about a robbery, the getaway, the pursuit, and the capture), the first use of title cards, an ellipsis, and a panning shot, and for its cross-cutting editing techniques. Jump-cuts or cross-cuts were a new, sophisticated editing technique, showing two separate lines of action or events happening continuously at identical times but in different places. The film was intercut from the bandits beating up the telegraph operator (scene one) to the operator's daughter discovering her father (scene ten), to the operator's recruitment of a dance hall posse (scene eleven), to the bandits being pursued (scene twelve), and splitting up the booty and having a final shoot-out (scene thirteen). The film also employed the first pan shots (in scenes eight and nine), and the use of an ellipsis (in scene eleven). Rather than follow the telegraph operator to the dance, the film cut directly to the dance where the telegraph operator entered. |

|

|||||

|

An Unseen Enemy (1912) d. D.W. Griffith Building upon what Edwin S. Porter had accomplished, director D.W. Griffith began to establish the basic vocabulary of film-making and editing. In this Biograph melodrama short (17 minutes long), he used the close-up of a gun emerging from a stove-port hole in a wall to intensify the emotional effect upon the two adolescent sisters (Lillian Gish and Dorothy Gish in their film debuts). The gun was menacingly brandished by their drunken housekeeper ("slattern maid") who was attempting to steal their inheritance money by locking them in a room, as they frantically phoned for help to be rescued. |

|

|||||

|

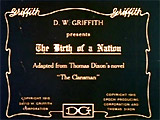

d. D.W. Griffith Griffith's controversial, explicitly racist, but landmark American film masterpiece was remarkable for bringing together many new cinematic innovations and refinements, technical effects and artistic advancements, including a color sequence at the end. It had a major formative influence on future films and has had a recognized impact on film history and the development of film as art. Its pioneering technical work, often the work of Griffith's under-rated cameraman Billy Bitzer, included many techniques that are now standard features of films, but first used in this film. Griffith brought all of his experience and techniques to this film from his earliest short films at Biograph, including the following:

|

|

|||||

|

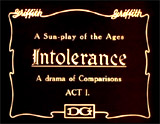

Intolerance (1916) (aka Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages) d. D.W. Griffith Griffith's expensive, most ambitious silent film masterpiece was one of the milestones and landmarks in cinematic history. Many reviewers and film historians consider it the greatest film of the silent era; four widely separate, yet paralleled stories were set in different ages - and in the original print, each story was tinted with a different color. Interwoven into the 4 stories, spanning several hundreds of years and cultures, were themes of intolerance, man's inhumanity to man, hypocrisy, bigotry, religious hatred, persecution, discrimination and injustice achieved in all eras by entrenched political, social and religious systems. The four historical periods were

In his radically non-linear, hybrid film, Griffith simultaneously cross-cut back and forth and interweaved the segments over great gaps of space and time - there were over 50 transitions between the segments. The symbolic bridging device that interconnected and linked together the various stories was the recurring cameo shot of Lillian Gish, his greatest star, as Eternal Motherhood. She endlessly and eternally rocked a cradle, accompanied by the title from Walt Whitman's poem Leaves of Grass: "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking. Uniter of Here and Hereafter - Chanter of Sorrows and Joys." Using cinematic methods ahead of their time and influencing a whole generation of future film-makers, he included a crane shot and spectacular crowd scenes and exterior sets (and live elephants!) for the fantastic Babylonian sequence. The innovative finale was an overwhelming, rhythmic, conglomerate sequence which placed all four stories into a stirring, fast-moving and exciting climax - as the suspenseful drama began to conclude, the cross-cutting increased in tempo and rapidity with shorter and shorter segments of each tale flowing together.

All of the same cinematic tools that Griffith had used in The Birth of a Nation (1915) (see above) were present in this film too. |

|

|||||